The Legal Rights of Nature: An Ethical and Critical Perspective

Introduction

The notion of granting legal rights to nature has emerged as a revolutionary concept, challenging traditional legal frameworks and advocating for the protection of the environment through legal personhood (Stone, 1972). Proponents argue that recognizing natural entities like rivers, forests, and continents as legal persons can foster environmental stewardship. However, this paradigm shift raises profound ethical questions, particularly regarding its long-term impact on marginalized communities and the potential reinforcement of a divisive anthropocentric view of nature.

Ethical Implications of Nature’s Legal Rights

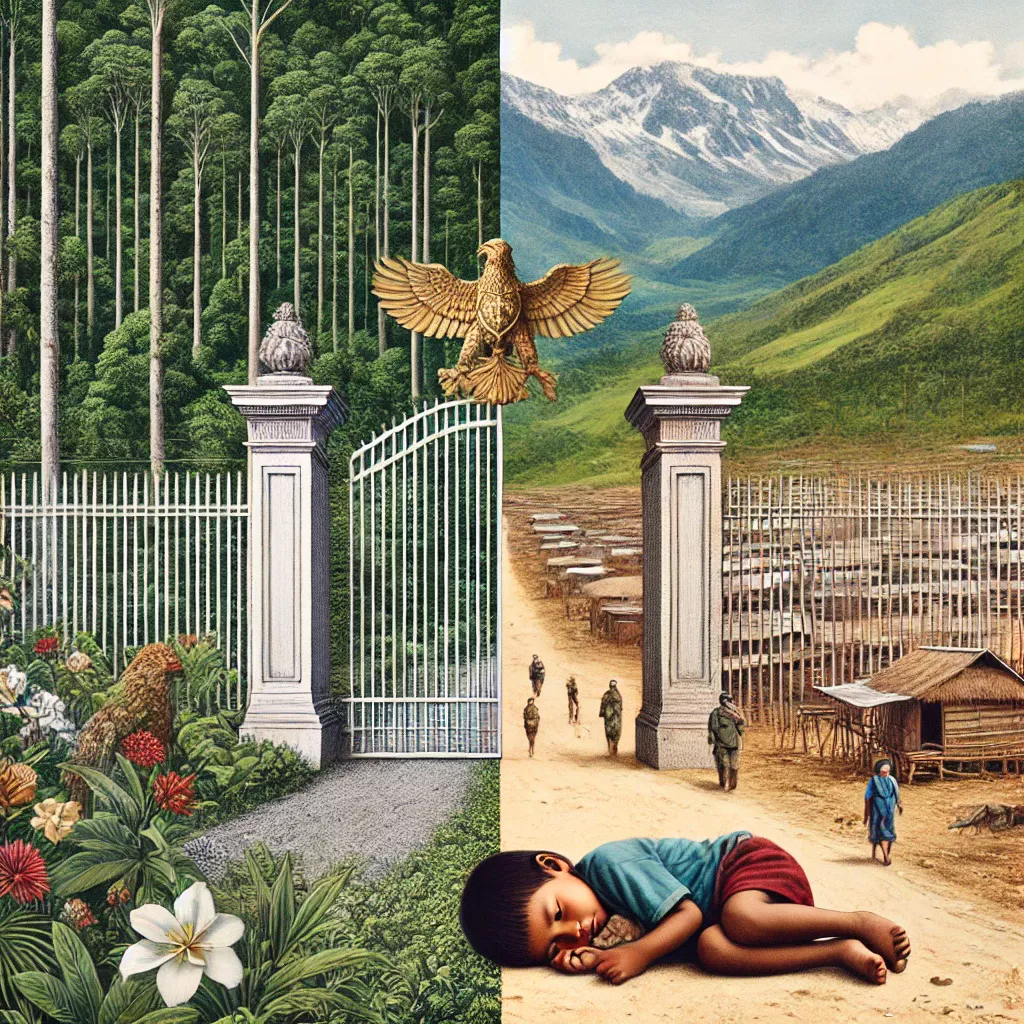

Granting legal rights to nature aims to protect ecosystems from exploitation, but it also perpetuates the dichotomy between humans and nature, reinforcing the notion that humans are separate from and superior to the natural world (Plumwood, 1993). This dualism can lead to an ethical paradox where the rights of nature are prioritized over human rights, particularly those of indigenous and marginalized communities who have historically coexisted with and depended on these ecosystems (Hernández, 2018).

Potential Harm to Indigenous Communities

The legal framework that seeks to protect nature’s rights could inadvertently marginalize communities that live in and rely on these environments. If nature is granted legal personhood, legal decisions could favor the protection of the environment over the rights of these communities, potentially leading to displacement and loss of livelihoods (Ruru, 2018). This approach could be manipulated by powerful corporations and NGOs, aligning with green capitalism agendas, where nature’s rights are exploited to monopolize resources, excluding local populations from decision-making processes.

The False Divide: Nature vs. Humans

The very concept of giving nature separate rights risks reinforcing a false dichotomy that views nature as an “other” to be protected from human interference (Latour, 1993). This perspective overlooks the interconnectedness of humans and nature, a relationship that many indigenous worldviews uphold. By enshrining nature’s rights in law, we may be undermining these holistic perspectives, potentially harming the very communities that have long been the stewards of these environments (Watson, 2016).

Conclusion

While the campaign for nature’s legal rights aims to promote environmental protection, it risks perpetuating a divisive and potentially harmful paradigm. The challenge lies in creating legal frameworks that respect both the rights of nature and the rights of human communities, particularly those who have historically been marginalized. Legal innovations must be critically examined to ensure they do not exacerbate inequalities or reinforce harmful anthropocentric views, but rather foster a truly inclusive and sustainable coexistence.

References

- Hernández, R. (2018). Environmental Justice and Indigenous Rights. Journal of Human Rights and the Environment, 9(1), 23-40.

- Latour, B. (1993). We Have Never Been Modern. Harvard University Press.

- Plumwood, V. (1993). Feminism and the Mastery of Nature. Routledge.

- Ruru, J. (2018). The Legal Voice of Nature. Environmental and Planning Law Journal, 35(2), 178-194.

- Stone, C. D. (1972). Should Trees Have Standing? Toward Legal Rights for Natural Objects. Southern California Law Review, 45(2), 450-501.

- Watson, I. (2016). Aboriginal Laws and the Sovereignty of Nature. Australian Feminist Law Journal, 42(1), 37-51.