The Role of Adrenaline and the Fight or Flight Response in Modern Human Stress

Introduction

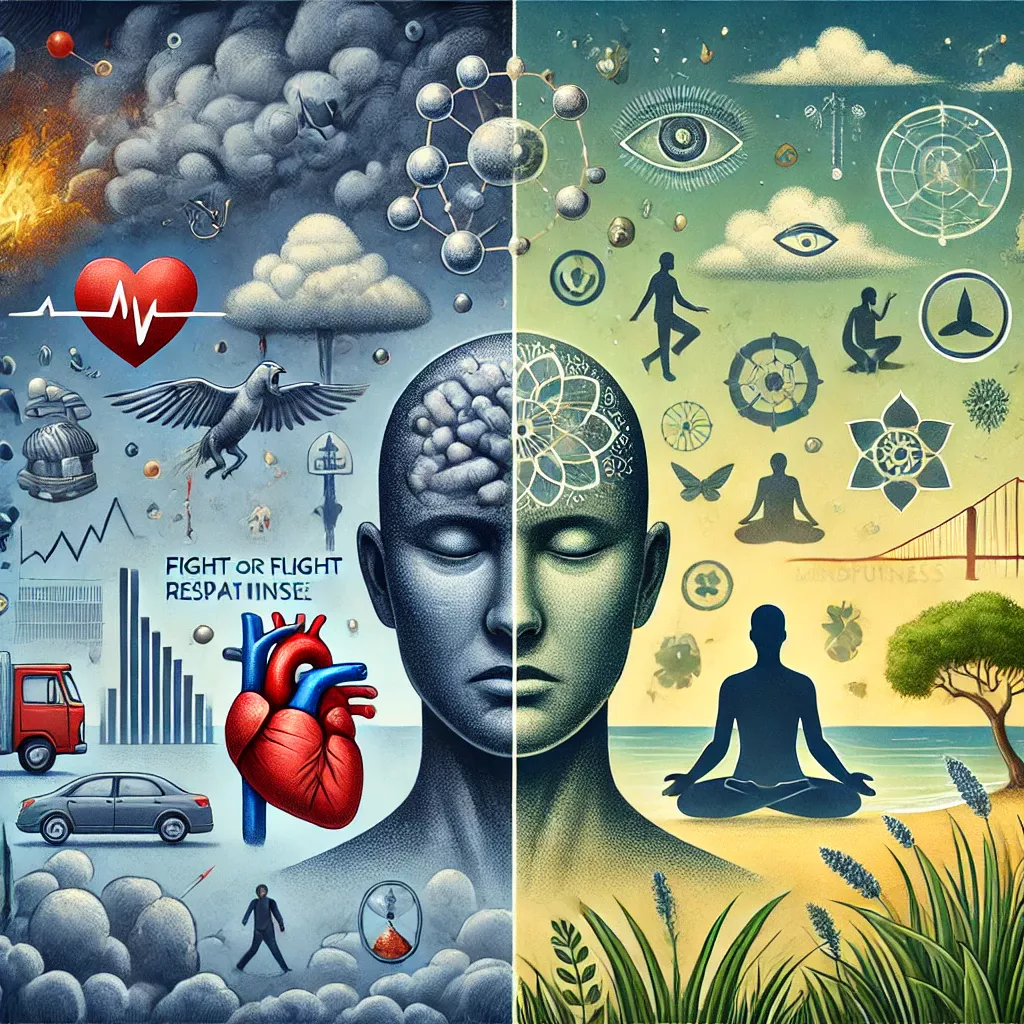

The fight or flight response is a physiological reaction that occurs in response to a perceived harmful event, attack, or threat to survival. This response was first described by Walter Cannon in the early 20th century and is characterized by the release of adrenaline (also known as epinephrine) and other hormones that prepare the body to either fight the threat or flee from it (Cannon, 1932). While this response was crucial for the survival of our ancestors in the face of immediate physical dangers, modern humans often experience this response due to psychological threats, such as work stress, economic uncertainty, and political turmoil. This article explores the role of adrenaline and the fight or flight response, how humans can consciously overcome these basic instincts, and the benefits of techniques such as meditation and mindfulness in managing stress.

Adrenaline and the Fight or Flight Response

Adrenaline, a hormone secreted by the adrenal glands, plays a critical role in the fight or flight response. It prepares the body for rapid action by increasing heart rate, dilating air passages, and mobilizing energy reserves (McCorry, 2007). This response is controlled by the sympathetic nervous system, which triggers the release of adrenaline in response to a perceived threat.

In the context of modern life, the fight or flight response can be triggered by non-physical threats, such as a looming deadline at work, financial instability, or political unrest. These stressors can cause the body to remain in a heightened state of alertness, leading to chronic stress. Chronic activation of the fight or flight response can have detrimental effects on health, including increased risk of cardiovascular disease, weakened immune function, and mental health disorders such as anxiety and depression (Chrousos, 2009).

Overcoming Basic Instincts Through Rational Thought

Unlike our ancestors, modern humans possess the cognitive ability to reflect on and regulate their emotions and responses. This capacity for self-regulation is rooted in the prefrontal cortex, the brain region responsible for executive functions such as decision-making, problem-solving, and impulse control (Miller & Cohen, 2001).

By engaging in rational thought and reflection, individuals can recognize when their fight or flight response is disproportionate to the actual threat and consciously choose a more appropriate reaction. This ability to override basic instincts with rational thought is a cornerstone of emotional intelligence and is essential for managing stress in a healthy way (Goleman, 1995).

The Impact of Chronic Stress on Health

Living in a constant state of fight or flight due to fears about the future can lead to chronic stress, which has been linked to numerous health problems. Chronic stress can cause dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, resulting in prolonged exposure to stress hormones like cortisol (Smith & Vale, 2006). This dysregulation can contribute to the development of various physical and mental health conditions, including hypertension, diabetes, depression, and anxiety (Sapolsky, 2004).

Moreover, chronic stress can impair cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and decision-making, further exacerbating the negative effects on an individual’s overall well-being (Lupien et al., 2009).

Meditation and Mindfulness as Stress Management Techniques

Meditation and mindfulness practices have gained widespread recognition for their effectiveness in reducing stress and promoting mental and physical health. These techniques involve focusing attention on the present moment and cultivating an attitude of non-judgmental awareness (Kabat-Zinn, 1994).

Benefits of Meditation and Mindfulness

- Reduction in Stress Levels: Studies have shown that meditation and mindfulness can significantly reduce levels of perceived stress and cortisol, the primary stress hormone (Goyal et al., 2014).

- Improved Mental Health: Mindfulness-based interventions have been found to reduce symptoms of anxiety and depression, enhance emotional regulation, and increase resilience to stress (Hofmann et al., 2010).

- Enhanced Cognitive Function: Regular meditation practice is associated with improvements in attention, memory, and executive functioning, which can help individuals better manage stress and make more rational decisions (Zeidan et al., 2010).

- Physical Health Benefits: Mindfulness practices have been linked to lower blood pressure, improved immune function, and reduced inflammation, which can mitigate the adverse effects of chronic stress on the body (Black & Slavich, 2016).

Conclusion

The fight or flight response, driven by the release of adrenaline, is a fundamental survival mechanism that has evolved to protect humans from immediate physical threats. However, in the modern world, this response can be triggered by psychological stressors, leading to chronic stress and associated health problems. By leveraging our cognitive abilities to override basic instincts and employing techniques such as meditation and mindfulness, individuals can manage stress more effectively, leading to better mental and physical health. Embracing these practices can help us live more calmly and centered in the present moment, rather than in a constant state of fear for the future.

References

Black, D. S., & Slavich, G. M. (2016). Mindfulness meditation and the immune system: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1373(1), 13-24.

Cannon, W. B. (1932). The wisdom of the body. W.W. Norton & Company.

Chrousos, G. P. (2009). Stress and disorders of the stress system. Nature Reviews Endocrinology, 5(7), 374-381.

Goleman, D. (1995). Emotional Intelligence: Why It Can Matter More Than IQ. Bantam Books.

Goyal, M., Singh, S., Sibinga, E. M., Gould, N. F., Rowland-Seymour, A., Sharma, R., … & Haythornthwaite, J. A. (2014). Meditation programs for psychological stress and well-being: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA Internal Medicine, 174(3), 357-368.

Hofmann, S. G., Sawyer, A. T., Witt, A. A., & Oh, D. (2010). The effect of mindfulness-based therapy on anxiety and depression: A meta-analytic review. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 78(2), 169-183.

Kabat-Zinn, J. (1994). Wherever you go, there you are: Mindfulness meditation in everyday life. Hyperion.

Lupien, S. J., McEwen, B. S., Gunnar, M. R., & Heim, C. (2009). Effects of stress throughout the lifespan on the brain, behaviour and cognition. Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 10(6), 434-445.

McCorry, L. K. (2007). Physiology of the autonomic nervous system. American Journal of Pharmaceutical Education, 71(4), 78.

Miller, E. K., & Cohen, J. D. (2001). An integrative theory of prefrontal cortex function. Annual Review of Neuroscience, 24(1), 167-202.

Sapolsky, R. M. (2004). Why zebras don’t get ulcers: The acclaimed guide to stress, stress-related diseases, and coping. Henry Holt and Company.

Smith, S. M., & Vale, W. W. (2006). The role of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis in neuroendocrine responses to stress. Dialogues in Clinical Neuroscience, 8(4), 383-395.

Zeidan, F., Johnson, S. K., Diamond, B. J., David, Z., & Goolkasian, P. (2010). Mindfulness meditation improves cognition: Evidence of brief mental training. Consciousness and Cognition, 19(2), 597-605.